- Home

- Reginald Kray

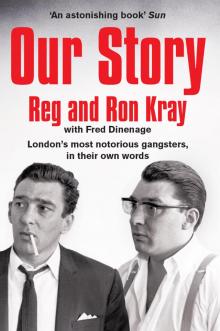

Our Story Page 9

Our Story Read online

Page 9

George Raft was a man Ron and I had admired in films when we were kids. Little did we think that many years later we would become his friends. We first met him at the Colony Club in Berkeley Square. He was aged about seventy-two then, and I have never seen a more smartly dressed man. He told me that he used to have one meal a day, a steak with salad every evening. He never smoked or drank. We took him around the East End and south London and he met our parents on several occasions. Shortly before he died he gave Ron and me a gold cigarette lighter each. He was a wonderful man.

It was George Raft who introduced me to Robert Ryan, whom I came to regard highly as an actor and as a man. I was with Ryan one night in the Colony Club when we were interrupted by Don Ceville, from the Canadian Mafia, who was over here hoping to do business with us. Ceville was an arrogant man and seemed very put out that Robert Ryan couldn’t recollect a meeting they’d once had in America. Hardly surprising when you think that an actor like Ryan must meet thousands of people every year. Ceville actually got quite nasty and I wondered if I was going to have to intervene, but Ryan handled the situation superbly, with great tact and diplomacy. Ceville eventually got the message and drifted away. I heard later that he had been gunned down in Toronto. I must say I wasn’t surprised. With his approach to life he was bound to come to a sticky end.

While I’m talking of friends I must mention Diana Dors and her husband Alan Lake. How sad that she should die and he should follow her in such tragic circumstances.

I first met Diana in the early sixties when Frances, who was then my fiancée, was dining with me at the Room at the Top in Ilford. We were both enthralled by this dynamic young singer and actress with the platinum blonde hair.

Diana became a good friend, in every sense of the word. We went out together many times, and when we were put away she would visit Ron, Charlie and me. Not only that, she would go round to see our parents in Vallance Road and make sure they were OK. She never went empty-handed. She always took them gifts and fruit and flowers. She was a bloody wonderful woman with an amazing zest for life, far more pure than her image and the media indicated, a woman with strong values and opinions, and devoted to her husband Alan and son Jason.

Alan, like us, suffered from what you might call a bad press. He was never the wild man the gutter press made him out to be. He was a kind, gentle bloke and a bloody good actor.

When I was at Parkhurst in the early days of the seventies I became friends with a con called Steve Tully, with whom I later became involved in a book about East End rhyming slang. Steve said he would like to meet Alan, so I wrote and asked him if he could come and see me. But the letter was intercepted by the governor, who told me that because I was a Category A prisoner I was allowed only to see visitors that the authorities thought I should see – and Alan Lake wasn’t one of them. I demanded an explanation, but never got one, though I suspect it was because Alan had strong contacts in the media and the authorities were afraid he would pass on stories to the papers about me.

To get round the problem, Steve Tully wrote to Alan, got a nice reply, and then sent him a pass to visit him. Steve and I arranged between ourselves that during Alan’s visit I would wander across the room to go to the toilet and stop and have a quick word with him, to shake him by the hand and thank him and Diana for their visits to our parents.

Alan travelled all the way down from London – and was then stopped at the main gate and told he couldn’t come in. The prison officers agreed that he had an official VO (visiting order), but as he wasn’t on Steve’s regular correspondence list he couldn’t come in. I tell you, there are some hard-hearted sons of bitches around, and they aren’t all criminals!

Steve and I were terribly disappointed and thought that Alan would be angry with us. All the time and money he’d spent coming down from London to see two gaolbirds, and then not being allowed in. Worse, being humiliated by a nobody in a uniform at the front door. Imagine our surprise then when we received a lovely letter from him saying how disappointed he was not to see us, how upset he knew we must be – but not one mention of the tiring journey down from London or the inconvenience. That shows you the kind of guy Alan was.

Poor Alan, he found life without Diana unacceptable. Sad, but understandable. It must have been like life without sunshine – and I know a bit about that.

Lenny Peters, the blind singer, I’ve already mentioned. When he first started, Ron helped him get an engagement at the Blue Angel in the West End and he often appeared at our clubs. Lenny has never forgotten and has even organized shows at Broadmoor for Ron and his friends.

Years ago, before I got put away, whenever I went into a pub or club or restaurant where Lenny was, he would always sense my presence in the room the moment I entered.

I can still remember a big charity night at the Cambridge Rooms, which Ron and I owned. Lenny was doing the cabaret and our guest of honour was the former heavyweight champion of the world, Sonny Liston. Now it was almost impossible to make Liston laugh and he was known as Old Stoneface. Yet, as he listened to a special song that Lenny had written about him, Old Stoneface just broke up with laughter. It was a magical moment.

This reminds me of another story about Sonny and Reg Gutteridge, the boxing writer and TV commentator and a member of a well-known London boxing family. Reg has only one leg. He lost the other during the war and in its place has a leg made of cork. One night he was in a club on the next table to Sonny Liston, who recognized him but couldn’t recall Reg’s name. He certainly didn’t know that Reg had a cork leg. Liston made a few snide remarks about the ‘white commentator’ and kept on until Reg, who had had enough, suddenly jumped up, picked up a knife and plunged it through his trousers and into his leg (the cork one, of course).

‘Go on then, Mr Liston,’ said Reggie, ‘you think you are tough – you stick a knife in your leg.’

Sonny Liston almost went white. Later Reg revealed his secret and he and Liston became friends. In fact, whenever Liston saw Reg he would insist on a repeat performance. In the end Reg had to refuse – he was running out of cork!

Yes, great days and great people. It’s often said the sixties were a special time, and it’s true. Friends Ron and I made in the sixties are still among our closest friends today.

Among them is Joe Pyle, whom we first met in the Double R. He was a promising middleweight boxer who was arrested for the alleged murder of a fellow by the name of Cooney, who’d been shot dead in the Pen Club near Spitalfields Market. Joe went on trial with others at the Old Bailey, but was acquitted. Today Joe is one of the biggest and most successful businessmen in London.

The last time I was outside with Joe, we had a drink at the Astor Club to celebrate the birth of his son. And these days Joe Junior, as well as Joe Senior, keeps in touch with me regularly.

Ron and I have made so many friends over the years – some good, some not so good, some loyal, some very disloyal. But of all the friends I’ve made – and this is no disrespect to my brother Charlie – the greatest friend I’ve ever had has been my twin brother Ron. When I was in Parkhurst I wrote a poem about friendship which I dedicate to him. Ron and I have been through so much, good times and bad, and always that amazing bond has been there between us. And it still will be on the day – God willing – when we are together again as free men.

Friendship

Friendship is

An eternity … of sorts

Valueless, unlike money,

A true friendship never aborts… his friend

Friendship is,

Stronger than steel,

Steel will break in the end,

But what better bond

Than a true friend?

Friendship is,

Entirely, utterly, selfless,

Helps you straighten out

When you are in a mess,

What more to say?

Friendship isn’t words, it’s feeling,

Sharing, caring

Understanding and believing!

&n

bsp; Friendship’s qualities

I can’t define,

But I have a friend called Ron

Who’s a true friend of mine,

And if you look closely

Ever so closely at Ron

You’ll see diamonds and gold

Are … as none,

When compared to the friendship

I share … with Ron.

4

RON: THE KILLING OF GEORGE CORNELL

The Blind Beggar public house in the Whitechapel Road in London’s Bethnal Green was not what you’d call an attractive pub. It was a big, ugly building in a very poor part of London. Not the sort of place you’d want to take a lady friend for a quiet drink or a business contact to clinch a big deal. It was simply the kind of pub where the poor people in that part of London would go for a drink to drown their sorrows or to have a bit of a knees-up on Saturday nights and pretend they were feeling happy.

But nonetheless the Blind Beggar will go down in the folklore of the East End for two reasons. First, so the story goes, it was named after a poem written in the seventeenth century and entitled ‘The Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green’. It tells how a blind beggar had a really beautiful daughter, but when the blokes who came to court her realized that she was the daughter of a mere beggar, they didn’t want to know her. She was beneath them. Then one day along came a young man who fell in love with her. He didn’t care that she was only the daughter of a beggar. He married her, and only then did the blind beggar reveal that he was a relation of the rich and powerful Simon de Montfort. The beggar, it seemed, was a rich man himself but didn’t want anyone marrying his daughter just for her money. So there was happiness – and money – all round. And the young girl had found true love and, presumably, lived happily ever after. It’s the sort of rags-to-riches tale that would thrive in such an area of broken dreams.

The other reason the Blind Beggar pub is part of the East End folklore is because of what happened between a bloke called George Cornell and me. It was in this pub that I shot Cornell dead. It was his death which helped bring to an end the reign of Reggie and me – and it was his death, as well as that of Jack McVitie, which has put us away for so many years. Probably, because of it, I shall finish up in Hell. Like my dear old Auntie Rose once told me, ‘Ronnie, love, you were born to hang.’

Yet I have no regrets. Cornell was a vicious, evil man. He lived by the gun and the knife and he deserved to die by them.

I knew from a very early age that I was going to kill someone. It was part of my destiny. And I always had this love of guns. I loved the feel of them, the touch of them, and the sound they made when you fired them.

I had shot one or two other men before I shot Cornell. With the others, though, it was always business and not personal. I always aimed to maim, not to kill.

With Cornell, though, it was different. It had become personal as well as business, and – I make no bones about it – I intended to kill him.

I had known George Cornell for a very long time, right back to when we were both tearaways in the East End. In those days he went under his real name of Myers. He probably changed it later to confuse the police. Even in those early days he was a loner and a really mean bastard. But he left us well alone and we left him alone. There was no point in looking for trouble, especially with someone you knew could handle himself.

We had our first real conversations when we were both in Winchester prison as young men. I was there after my mind had gone funny at Camp Hill, he was there for assault. He already had a long record of violence and had been given three years for slashing a woman friend with a knife. She’d said something out of turn and Cornell had gone for her. He had a very short temper and, as was proved later, he enjoyed seeing other people in pain.

When we were at Winchester he told me that he’d got himself into the pornography business and there was a lot of money to be made in it – not only from selling the stuff but also in blackmailing the weak bastards who had bought it. He said he was looking for a partner, but I told him I wasn’t interested.

Years later – and this is not generally known – Cornell and I had another conversation in which he admitted to me that he had killed a man. It has long been a mystery what happened to a London gangster called Ginger Marks, who disappeared around 1962. Cornell told me he had shot Marks ‘in the head’ in a house in Cheshire Street, a road near our home in Vallance Road. He said he had blown Marks’s head clean away. But he wouldn’t tell me what he’d done with the body, although he did say he’d got rid of it himself.

Well before that, I can remember Cornell and Marks having a blazing row in a pub called the Grave Maurice. I had stepped in between them as I could see it was getting really nasty. I acted as a peacemaker and got them to shake hands. Cornell told me then that he hated Marks and that one day he would ‘blow his head off’. I think Cornell was afraid of Marks because Marks always carried a gun. But Cornell swore to me that he was the man who killed Marks.

When Cornell really began to be a problem for us was when he moved south of the river and joined forces with the Richardson gang. This was run by two brothers, Charlie and Eddie, in conjunction with a man known as Mad Frankie Fraser. The Richardsons ran a highly successful scrapyard in Brixton in south London. They made a really good living from it. But Charlie and Eddie were always fascinated by the low life, by doing deals, by making money, by cheating the system. So they began putting together an army of crooks and hardmen. They were thought to have moved into the protection business and other shady deals. It was said that at one time they owned a mine in South Africa, though, like us with our African dealings, they were cheated out of a fortune. It was also said they owned a bank in Mayfair, though I don’t know if that is true. What is true is that they were a mightily powerful and feared organization. Feared because if anyone crossed them the Richardsons were ruthless in their retribution.

Some of the techniques used by the Richardson gang made the Kray twins look like Methodist lay preachers. Whereas we believed that a good thick ear or a punch on the jaw would persuade most people round to our way of thinking, the Richardsons had different ideas. It was claimed that they believed in torture and would torture anyone who got in their way or anyone they suspected had been disloyal to them. Even our guys were scared stiff they’d fall into the Richardsons’ hands. None of them went south of the river unless they had to, and then they’d scurry back as quick as they could when their business was finished.

There was a sort of truce between us and the Richardsons, based on the premise that they would stay south of the river and we would stay the other side. But it was always an uneasy truce and I had a gut feeling that something or someone would force us into a full-scale war.

That someone turned out to be George Cornell. He moved south and became the Richardsons’ chief hatchet man and torturer. He was extremely well qualified for the job.

We had spies in the Richardson camp and it wasn’t long before we started hearing stories that Cornell was stirring things up for us. He kept on at the Richardsons and Mad Frankie to move into our territory and wipe us out for good. That would have made the Richardson gang, along with Cornell and Fraser, the kings of London. It was a situation that we could not tolerate. It was also beginning to affect our own business affairs. We were in the early stages of negotiations with the American Mafia at the time and even they got uneasy because they could smell trouble in the London air.

The trouble might still have been avoided, but then Cornell did the most stupid thing he’d ever done in his life. In front of a table full of villains he actually called me a ‘fat poof ’. He virtually signed his own death warrant.

It happened just before Christmas, in 1965. We had decided to call a meeting with the Richardsons to try to cool things down. We had already had one meeting with John Smith, a top Mafia man from New York, at which the Richardsons had been present, and that had ended unpleasantly with certain remarks aimed at our American guest. But there had to be some sort of d

eal worked out with the Richardson gang, otherwise it was obvious that a full-scale gang war was going to start, and that would have done no one any good. So we arranged a meeting at the Astor Club, off Berkeley Square. We went there with two of our right-hand men, Ian Barrie and Ronnie Hart. Charlie and Eddie Richardson were there with Mad Frankie Fraser and the inevitable George Cornell.

It soon developed into a very stormy meeting, mainly over how much of the action the Richardsons were going to get in our dealings with the Americans. We didn’t want them to have any, but knew we might have to compromise to avoid any bloodshed. Cornell, of course, couldn’t resist sticking his oar in, time and time again, even though it was strictly none of his business. The negotiations were actually between the Krays and the Richardsons – the others were there merely for protection, to keep a watching brief. But Cornell was doing his best to stir things up. He said we were fannying (talking a load of rubbish). Then he did a very stupid thing. In front of all those people – our own men and top men from the other side – he said, ‘Take no notice of Kray. He’s just a big, fat poof.’ From the moment he said it he was dead.

After that meeting the troubles and the aggro really began. It was suddenly all about who were the top dogs in London – who were the real kings of the underworld. It was a test of strength and nerve. A few days after that meeting a car mounted a pavement in Vallance Road and knocked down a bloke who looked and was dressed very much like me. It could have been coincidence, but we didn’t think so. Now we were completely on our guard. We sensed that full-scale war was on the cards.

Our Story

Our Story