- Home

- Reginald Kray

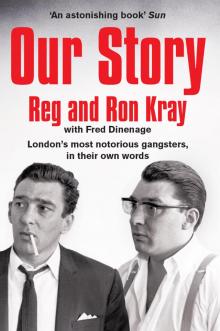

Our Story

Our Story Read online

REG AND RON KRAY

OUR STORY

London’s most notorious

gangsters, in their own words

with Fred Dinenage

PAN BOOKS

To our mother

Our Mum

Mum you are like a rose.

When God picked you, you were the best mum

he could have chose.

You kept us warm when it was cold

With your arms around us you did fold.

For us you sold your rings of gold.

When you died, I like a baby cried.

When I think of you it is with pride,

So go to sleep mum I know that you are tired.

Ron

CONTENTS

Introduction (Reg)

Foreword (Fred Dinenage)

1 Memories of an East End Childhood (Reg and Ron)

2 Crime and Punishment (Reg and Ron)

3 The Swinging Sixties (Reg)

4 The Killing of George Cornell (Ron)

5 The Truth about the Mad Axeman (Ron)

6 The Last Supper – the Killing of Jack McVitie (Reg)

7 The Trial and the Traitors (Ron)

8 The Women We Loved (Reg and Ron)

9 Life in Parkhurst (Reg)

10 Life in Broadmoor… ‘Without my drugs I go mad’ (Ron)

11 Life in Gartree (Reg)

12 Poetry and Painting (Ron)

13 Just a Thought (Reg)

A Final Word (Fred Dinenage)

INTRODUCTION

‘I sentence you to life imprisonment, which I would recommend should not be less than thirty years.’

So said Mr Justice Melford Stevenson to the Kray twins, Reggie and Ronnie, at the Old Bailey, on 8 March 1969. They had been found guilty of the gangland killings of George Cornell and Jack ‘The Hat’ McVitie. The twins were thirty-four. At the time of the publication of this, their own story, they are fifty-four. They still, therefore, officially have ten years left to serve.

Most of Reggie Kray’s twenty years in captivity have been spent as a Category A prisoner in the maximum-security Parkhurst prison near Newport on the Isle of Wight. At the time of writing he is at maximum-security Gartree prison near Market Harborough in Leicestershire. Despite repeated appeals he has been given no official indication that he will serve anything less than the thirty years to which he was sentenced.

His brother Ronnie began his sentence at Durham gaol, was then transferred to Parkhurst after a campaign led by the twins’ mother, but has spent the last sixteen years at Broadmoor maximum-security psychiatric hospital near Crowthorne in Berkshire. He believes that he will never be released.

Fred Dinenage

FOREWORD

As the old cliché has it, there are three ways out of the gutter for kids from the ghetto: boxing, singing and crime. For Reg and Ron Kray, boxing was their first choice. Both boys were handy with their fists, both were promising fighters, and both trained at the Repton Boys’ Boxing Club – London’s oldest boxing gym, established in 1884 and still standing today. It was at this gym that I interviewed one of the Krays’ most feared gangland rivals, Mad Frankie Fraser, for Sky’s documentary, The Krays. Fraser was full of praise for Reg and Ron and recalled watching as the twins fought each other in the backyard at their home when they were lads.

‘They were fearless little bastards,’ said Frankie, ‘and they were knocking shit out of each other. Both of ’em could have been champions but they kept getting into bother with the law. In the end the pair of ’em were blacklisted and that was the end of their boxing.’

Fraser revealed that the Krays had tried to persuade him to leave their rival Charlie Richardson’s gang and join them. ‘But I decided not to,’ said Frankie. ‘I liked the twins but I thought Charlie had got more brains. I thought he was more of a businessman.’ Fraser, despite various altercations with the Krays over the years, ended up being close friends with the twins, especially Ron, with whom he spent several years at Broadmoor.

So, professional boxing was out for the twins, and they couldn’t sing, but their fame as gangsters has kept them in the public eye in this country for as long as Sixties icons The Beatles and Elvis Presley. I am always amazed by, not only how well remembered the Krays are by people who were around in the sixties and seventies, but how widely their name is known among younger generations who seem to endlessly devour books, films and TV shows about the brothers. The documentary I made for Sky about the Krays has been repeated several times and, as I write, is still being shown. When first transmitted, it attracted the biggest audience Sky’s Crime Investigation channel had ever known. And the Krays’ fame is not confined to the UK. Their name is known on the Continent, in Australia and, thanks to the Kemp brothers’ 1990 film, in the US. Our Story, when first published, spent several weeks at the top of the Sunday Times bestseller list.

What is their long-lasting appeal? Why are they still so famous? Why do people, young and old, find their story so engaging years after they ruled the streets of the East End and years, even, since they both died? Maybe it’s nostalgia; a memory of a time when life seemed simpler, less complicated. But while some are quick to mythologize the brothers, others are less positive about Reg and Ron Kray. The family of Reggie’s beautiful wife Frances, who died aged twenty-four, are among them. Many of Frances’ family have their own beliefs about what happened to her. There are even unproven theories that she was murdered.

Many of the Krays’ own gang, known as the Firm, also have bad memories of the brothers – particularly Ron. I spoke to one former member in the Carpenters Arms, the pub bought by the twins for their mother. It’s in Cheshire Street, just a hundred yards from their old home on Vallance Road. Today it’s considered a trendy place; back then, it’s been claimed, the counters were made of coffin lids.

The former Firm member told me: ‘I fell out with Ronnie but then I got a message to meet him in a flat. I thought we were going to talk things over, get things sorted. But when I got there he was with some other guys from the Firm. Ron started to slag me off. He was screaming and shouting. Saliva was coming out of his mouth. Then the guys held me down while Ron got a red-hot poker from the fire and held it against my face. I screamed and screamed. I’ve still got the scar. But Ron just fucking laughed. He was a cruel bastard.’

Working on this book with the Kray twins was never going to be easy. That was the warning I was given by several people, including the governor of Parkhurst Prison, and the Medical Director at Broadmoor Hospital for the Criminally Insane.

The project began in 1985 after Reg saw a programme I had hosted on Coast to Coast, the nightly news listing for the south of England. I remember the report vividly. It featured the father of a young girl whose life had been saved by a kidney transplant. To show his thanks he wanted to raise money to buy some specialized equipment for the hospital. A couple of days after the programme had aired I received a letter franked by HMP Parkhurst. It was from Reg Kray. The writing, difficult to decipher because of the scrawling hand that Reg shared with his brother, said, ‘I watched the film on your programme. I would like to help. There are some talented artists here in Parkhurst. You could sell some of their paintings to make some money.’

I confess I was a little startled to receive this letter. I was aware of the Krays, of course. I was a young man in the fifties and early sixties when they made headlines as they ruled the streets of London and were finally sent down by Leonard Nipper Read. Nipper Read was a Chief Superintendent on the Met’s Murder Squad in the mid-sixties and dedicated his life to bringing down the Kray twins. Ironically, he shared their love of boxing and he was once even chairman of the British Boxing Board of Control. The name Kray was, at that time, still powerful enough to create a certain amount of apprehen

sion. But, as a journalist, it was an invitation I couldn’t refuse.

After a few weeks, thirteen paintings arrived at our studios in Southampton. Twelve of them were very good. The thirteenth was a childlike painting of two boxers in a ring, signed R. Kray. In terms of technique, it was atrocious, but it was the top seller at the auction and has since been sold on for even more money. We ran another item on Coast to Coast about the auction and, a few days later, I received another letter from Reg: ‘Why don’t you come and visit me at Parkhurst?’

A few weeks later I found myself on the Cowes ferry from Southampton, en route to the prison. Wemet in the visiting hall, a noisy, rowdy, unsettling barn of a room, packed with prisoners and their visitors. Reg was smaller than I expected but well-muscled and toned. Hours spent in the gym had left him looking younger than his years. He had a charismatic air about him. You knew you were face-to-face with a man you wouldn’t want to mess with. He was flanked by two or three tough-looking young men, fellow cons who acted as his bodyguards.

‘I need them,’ he told me as he sat down. ‘There’s a lot of psychos in this place who’d like to get me ’cos I’m the main fucking man.’ Then he said, ‘Me and my brother Ron want to write our book. There’s been a lot of shit written about us. We’d like to put the record straight. Do you know anyone who could write this book?’ I replied that I thought I could do it.

But before anything, I had to meet Ron. Reg had said to me: ‘If Ron likes you, you can do the book. If not, we can’t go ahead.’ Getting permission to visit Ron took time. The authorities did not seem keen on a journalist visiting Broadmoor, a high security psychiatric hospital that houses some very high-profile prisoners. Finally, though, the accreditation arrived.

My first visit was on a sunny, but bitterly cold, winter’s morning. Broadmoor is a bleak and dark Victorian building which has been modernized now but was then a forbidding place. I parked my car and walked alongside the high walls with barbed wire atop towards the huge brown wooden doors at the front of the hospital. As I approached the doors I was aware of a car driving very slowly beside me. I stopped and looked over my shoulder. The car stopped too. It was a white Rolls Royce with blacked-out windows. One of its rear windows lowered slightly and a puff of cigar smoke blew out.

‘Fred Dinenage?’

‘Yes,’ I replied.

‘I’m a close friend of Ronnie Kray,’ the voice said, ‘and I believe you’re gonna write a book about him.’

‘Well, I hope so,’ I replied.

‘And I hope that if you do, it will be fair and honest.’

‘It will be,’ I said.

‘Good,’ the voice said, ‘because I will be watching.’ And with that, the window closed and the car pulled smoothly away. At this stage I was beginning to wonder what the hell I was letting myself in for. But it was a case of no turning back. As a journalist, I was intrigued to find out where all this was going to lead.

I learned later that the voice was Joe Pyle, also known as Big Joey, a major player in the London crime scene at the time. He had been the best man at Ronnie Kray’s first wedding and was a highly respected gangland figure. In the early sixties he went on trial for the murder of a nightclub owner but was acquitted. In the eighties he was arrested over a multi-million pound cannabis smuggling charge but again went free after a key witness refused to testify. Finally, in 1992, he did go down – for masterminding a huge drug ring. He served five years and died in February 2007.

Once inside Broadmoor’s forbidding front doors I was taken to meet the hospital’s medical director who told me, ‘You’ll find Ron Kray a perfectly pleasant man. But he is a sick man, a chronic paranoid schizophrenic. His mood swings and paranoia are controlled by strong medication. The medication lasts for approximately forty days. Unluckily for you, he is now on day thirty-nine. He will be fine in general conversation but if he is unhappy with things his right leg will begin to shake. If that happens it’s better for you to change the subject. Quickly.’

I was taken to Broadmoor’s visiting hall – large, cold, paint peeling off the walls, plastic chairs and tables. I was shown to a table in the middle of the room and told to wait. After a few minutes, I heard the sound of two marching feet. It was Ronnie Kray. He marched everywhere, earning himself the nickname The Colonel. He was immaculately dressed in well-polished brogues, a brown suit, white shirt and brown tie with his hair brushed tightly to his head. He was wearing spectacles and was smaller and thinner than I’d expected. We shook hands and he sat down. He summoned another patient who, it turned out, acted as his personal butler. Ronnie ordered a non-alcoholic lager and some cigarettes for himself and a pot of coffee for me. I later learned that this butler was in fact a double murderer who’d knifed two people to death on a railway platform because he ‘didn’t like the way they were looking’ at him.

We chatted happily enough, Ronnie swallowing his lager and chain-smoking. Never more than two or three puffs on each cigarette before he stubbed it out in the ashtray. The conversation centred on my recent visit to Reg in Parkhurst. Ron wanted to know how he was and what he’d been saying. Ron was also interested in me. Was I married? Did I have children? Finally, he asked, ‘This book you want to write. What are you going to put in it?’

‘The usual things, I suppose,’ I replied, ‘the things that have been in other books. But I will have to ask you certain questions.’

‘What sort of questions?’ he asked, staring straight into my eyes.

‘Well,’ I replied, a bit nervous at this point, ‘things like what happened to Frank Mitchell, the Mad Axeman.’

Ronnie’s right leg began to shake uncontrollably. I swiftly turned the conversation to the lovely weather we were having for the time of year. We chatted on and Ron must have liked me because he eventually agreed to let me write the book. I continued to visit him on a monthly basis. We usually met in that visiting hall. Later, Peter Sutcliffe, the so-called Yorkshire Ripper, would regularly appear on an adjoining table, always with a couple of young women – groupies – holding his hand. But he was not allowed to talk to Ron Kray. Not even allowed to look at him. The Krays had no time for men who hurt women or children.

Once, I was allowed into Ron Kray’s hospital room, which was more like a prison cell with iron bars at the window, a table and an iron bed. Later, when Broadmoor began its modernization programme, he was moved to a proper bedroom. I was able to visit both brothers for roughly two hours a month. It was the first time they had opened up to a journalist in all the years they had been inside. Their natural instinct was to mistrust anyone in the media. Probably with good cause; they certainly felt the press had given them a rough deal and that most of the books written about them had done them a grave injustice.

I never had a problem on a personal level with either of the Kray twins, although they weren’t the easiest to work with professionally. They constantly wanted things in the book to be changed. This was generally because on one occasion they would slag off some friend or foe, and then, on the next occasion, be full of praise for them. Something would have happened in the meantime to change their opinion. This was very much the way with Reg or Ron. You were either in or out. There was no halfway house. They could take offence very easily and then, conversely, they could be extremely generous. They were, without doubt, creatures of mood. And, at the end of it all, they never said whether they liked the book or not. The only disagreement we had was over which newspaper would serialize the book. Three newspapers wanted the rights: the Sunday Times, News of the World and Sunday Mirror. At the time, both Reg and Ron were desperate to lose their hoodlum image – to become more serious, more accepted. With this in mind, I urged them to choose the Sunday Times. But Reg and Ron eventually went for the bigger money and chose the News of the World. Money, incidentally, which they would give away – often to deserving causes. When they died they were both broke.

In the week of the first serialization Ron rang me up and asked: ‘They will treat it sensitively, won’t th

ey?’

‘Well, I’ll ask them,’ I said, ‘but with the News of the World you can never be sure.’

I did as promised but the following Sunday the newspaper appeared with a caricature of Ron on the front page, with the headline, RONNIE KRAY SAYS I’M MAD AND GAY.

Ronnie was mad, alright. With me. But it didn’t last. I received criticism from some for writing the book and the Krays were criticized because they received money for it. Since their story was published there have been other books and other accusations about them. Neither of the Kray twins are around now, of course, to defend themselves. Neither is Big Joey, although after Our Story was published he did ring me up. He said simply: ‘Well done. It’s fair and honest.’

And the Kray twins’ legacy? A simple message to any who would seek to follow in their footsteps – Don’t do it. It’s the oldest cliché in the book but still one of the truest: Crime doesn’t pay. It didn’t for Reg and Ron Kray. They died broke, in pain and embittered. The only consolation they had is that their memory lingers on.

1

MEMORIES OF AN EAST END CHILDHOOD

REG: BORN TO BE VIOLENT

I was born to be violent. When I was young most of my violence happened in the boxing ring. I was good enough to have become a great champion, but something happened to me when I was about eight years old which, looking back, was an omen – a sign of the bad things to come. That was when I was involved, for the first time, in the death of another person.

I have never revealed this before – to anyone. I have carried it around in my heart for fifty years. Even though I have been through many bad experiences in my life and seen a lot of bloodshed, the worst experience I ever had happened to me when I was just a kid of about eight years of age. I was involved in a terrible accident that caused the tragic death of a six-year-old boy. The experience has been deeply etched into my mind and even today, all these years later, I feel a great sorrow whenever I think of what happened.

Our Story

Our Story