- Home

- Reginald Kray

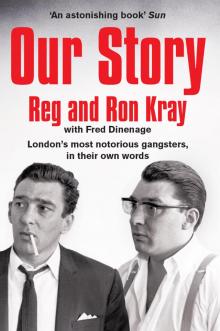

Our Story Page 10

Our Story Read online

Page 10

And do you know what? Despite the fact that the aggro was screwing up our American deals, because the Yanks didn’t want to know when they could sense there was trouble in the air, despite all that, I was loving it. This, to me, was what being a gangster was all about. Fighting, scrapping, battling – that’s what I’d come into it for in the first place. Don’t get me wrong. I didn’t want to kill people – I just wanted a bloody good scrap. Just like we did when we were kids.

But in March 1966 the Richardsons went and spoiled it all. They made a complete bollocks of the whole thing. For some reason they launched a full-scale attack, guns blazing, on a club called Mr Smith’s in Catford. No one really knows why. We might have had a small financial interest in the club, but nothing heavy, nothing serious. Some said that the Richardsons had been tipped off that Reggie and I and half our firm would be in the club that night, and that was why they hit it. But only one member of our firm was there at the time – a young guy called Richard Hart, who was having a quiet drink. He was an extremely nice fellow, with a wife and little kids, but they shot him dead.

As it happened, the Richardsons, Frankie Fraser, Cornell and the rest of them got more than they had bargained for that night. Mr Smith’s was full of gangsters, guys who could really handle themselves, and when the Richardsons burst in with knives and shooters these guys hit back. There was one almighty battle and Eddie Richardson and Frankie Fraser were badly wounded. They were also arrested, along with Charlie Richardson. Typically, the one who slipped through the police net, the snake who slithered away through the grass, was George Cornell.

Richard Hart had to be avenged. No one could kill a member of the Kray gang and expect to get away with it. The problem was, both of the Richardsons and Mad Frankie Fraser were in custody and likely to remain so. That left Cornell. He would have to be the one to pay the price. And, let’s face it, who better? All I had to do was find him. The next night, 9 March, I got the answer. He was drinking in the Blind Beggar.

Typical of the yobbo mentality of the man. Less than twenty-four hours after the Catford killing and here he was, drinking in a pub that was officially on our patch. It was as though he wanted to be killed.

I unpacked my 9mm Mauser automatic. I also got out a shoulder holster. I called Scotch Jack Dickson and told him to bring the car round to my flat and to contact Ian Barrie, the big Scot, and to collect him on the way. As we drove towards the Blind Beggar, I checked that Barrie was carrying a weapon, just in case.

At 8.30 p.m. precisely we arrived at the pub and quickly looked around to make sure that this was not an ambush. I told Dickson to wait in the car with the engine running, then Ian Barrie and I walked into the Blind Beggar. I could not have felt calmer, and having Ian Barrie alongside me was great. No general ever had a better right-hand man.

It was very quiet and gloomy inside the pub. There was an old bloke sitting by himself in the public bar and three people in the saloon bar: two blokes at a table and George Cornell sitting alone on a stool at the far end of the bar. As we walked in the barmaid was putting on a record. It was the Walker Brothers and it was called ‘The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Any More’. For George Cornell that was certainly true.

As we walked towards him he turned round and a sort of sneer came over his face. ‘Well, look who’s here,’ he said.

I never said anything. I just felt hatred for this sneering man. I took out my gun and held it towards his face. Nothing was said, but his eyes told me that he thought the whole thing was a bluff. I shot him in the forehead. He fell forward onto the bar. There was some blood on the counter. That’s all that happened. Nothing more. Despite any other account you may have read of this incident, that was what happened.

It was over very quickly. There was silence. Everyone had disappeared – the barmaid, the old man in the public and the blokes in the saloon bar. It was like a ghost pub. Ian Barrie stood next to me. He had said nothing.

I felt fucking marvellous. I have never felt so good, so bloody alive, before or since. Twenty years on and I can recall every second of the killing of George Cornell. I have replayed it in my mind millions of times.

After a couple of minutes we walked out, got into the car and set off for a pub in the East End run by a friend called Madge. On the way there we could hear the screaming of the police car sirens. When we got to the pub I told a few of my friends what had happened. I also told Reg, who seemed a bit alarmed.

Then we went to a pub at Stoke Newington called the Coach and Horses. There I gave my gun to a trusted friend we used to call the Cat and told him to get rid of it. I suddenly noticed my hands were covered in gunpowder burns, so I scrubbed them in the washroom. I showered and put on fresh clothing – underwear, a suit, a shirt and tie. (We had spare sets of ‘emergency’ clothes at several places.) All my old clothing was taken away to be burned. Upstairs in a private room I had a few drinks with some of the top members of the firm – Reg, Dickson, Barrie, Ronnie Hart and others. We listened to the radio and heard that a man had been shot dead in the East End. As the news was announced I could feel everyone in the room, including Reg, looking at me with new respect. I had killed a man. I had got my button, as the Yanks say. I was a man to be feared. I was now the Colonel.

Later that night we were having a party at a flat we owned in Lea Bridge Road, when the Flying Squad came pouring in. We’d been expecting them. After all, by now the whole of London knew who’d killed George Cornell. But, of course, the police had to prove it. There could only have been four witnesses – the barmaid, the old man and the other two blokes. A representative of the firm had already been to see them all. We were fairly confident that none of them would talk. Over confident, as it turned out a few years later.

I was taken to Commercial Road police station in Stepney and Reg was taken to Leyton police station. I was put in an ID parade. Two men walked by but they didn’t pick me out.

Then in came Detective Chief Superintendent Tommy Butler, the man they called the White Ghost, who was later to hunt down all the so-called Great Train Robbers, with the exception of one Ronnie Biggs. He never did nail Biggs though he probably broke his heart and his health in trying. He was disappointed about not nailing me as well. ‘It’s not over yet,’ he said. ‘We may want to see you again. We’ll be in touch.’ But Butler never got in touch and shortly afterwards he must have been taken off the Cornell case. He, like the rest, found the Krays a difficult pair to nail.

I was a free man again. Only now there was a very big difference. I had killed a man, and everyone knew I had killed him, including the police. Now there was no doubt that I was the most feared man in London. They called me the Colonel because of the way I organized things and the way I enjoyed battles. It was a name that I loved. It suited me perfectly.

After Butler had released us, we stayed a few nights with our mum at Vallance Road, but one night Cornell’s widow came round and broke some windows and called us ‘murderers’. Naturally, our mother was upset. And so, too, was Mrs Cornell. That was why we let her off with damaging our house – something that no one else would have got away with. But we could understand her being over-wrought. After all, she’d lost her meal ticket when Cornell went down and she probably did love him in her own way. Of course, Mrs Cornell was told not to come round again, and that was the end of that.

It had been a wearying time, so Reg and I went away for a holiday in Morocco, where we stayed with Billy Hill and his girlfriend, Gypsy. We had a bloody marvellous time over there. Among the other guests were millionaire’s daughter Anna Gurber and her husband and the legendary Dandy Kim Waters. We had some wonderful parties and everything was fine until the Moroccan police came knocking on the door and told us to leave because we were ‘undesirables’. Obviously Scotland Yard was trying to put pressure on us, but that was all they could do. They had no evidence on the Cornell killing and no witnesses.

Unknown to us, of course, the police eventually did a very smooth job on the barmaid, persuading her to give evid

ence against us. She was a very silly girl but also a very lucky one. Lucky in as much as we could, with one phone call, have had her marked for life. But Reggie and I never hurt women or kids, no matter what the provocation. We only ever hurt other villains but even they, once we were arrested, were let off. It was as though we suddenly decided enough was enough.

Cornell was dead, the Richardsons and Frankie Fraser were locked up, and the Krays ruled London. Nothing at that stage could stop us. Everyone seemed frightened of us – people were actually ringing up begging to pay protection money!

Since those days Reggie and I have become friends of the Richardsons and Frankie Fraser. In 1969 Eddie Richardson and Reg were both in the special security block at Parkhurst. On one occasion Eddie went on hunger strike with the intention of bringing various complaints he had to the attention of the press. However, though he was officially on hunger strike, Eddie didn’t really want to starve, so Reg used to leave hard-boiled eggs for him behind the toilet seats to help stave off his hunger pains. And to think that only a few years earlier they had been such deadly enemies. What might have happened if we could have settled our differences and got together? We could have ruled Europe.

Reg also served time in Parkhurst with Eddie’s brother Charlie. They would discuss theories on positive mental attitude and things like that. Frankie Fraser was also at Parkhurst for a time but then he was moved to Broadmoor where he and I became very close friends. Reg and I also have a lot of admiration for Frankie’s sister, Eva. She travelled many miles to visit Frankie in various prisons but always found time to write to Reggie and me.

My brother Charlie met Frankie Fraser and the Richardsons socially not too long ago and I was pleased when Charlie told me that, despite the passing of the years, they all looked fit and well. Charlie Richardson was reminiscing about the time when he was in Shepton Mallett army prison with Reg and me all those years ago. So in the end all that animosity between us and Fraser and the Richardsons was unnecessary because they turned out to be such nice guys. There was just one bad apple in their team – George Cornell – and he upset the apple cart for everyone.

Cornell was unlucky – George Dixon was lucky.

After our problems with Esmerelda’s Barn we had taken over a club called the Regency in Stoke Newington. To be honest, it wasn’t much of a place, an illicit gambling club, but it made good money for us. It also attracted a fairly unsavoury sort of clientele, the sort with big money, big mouths and big fists. Occasionally I had to lay down the law and stop the worst offenders coming in. George Dixon, I decided, had to be banned because of his heavy drinking, and because I heard he’d been making comments about my sex life, something I always hated. He’d once been a friend but he was pushing friendship beyond the limits. So I barred him. But it made no difference.

I’m sitting in the Regency one night when in comes Dixon. He comes marching up to me, bold as brass, a very stroppy look on his face, and he says, ‘What’s all this then, Ron boy, stopping me coming in here? What’s your game?’

I could never stand being spoken to like that. I thought to myself that I would kill him. So I took a revolver out of my pocket, put it against Dixon’s head and pulled the trigger. Nothing happened. It didn’t go off. Dixon went white, screamed and ran out of the club. He never came back. I used to have a fellow drive me about, named John, from Canning. I took the bullet that didn’t fire out of the revolver and gave it to the fellow who drove me about, telling him to give it to Dixon. I told him to tell Dixon he must have nine lives, like a cat.

Since then I have again become friendly with Dixon and his family and they come to visit me in Broadmoor. I have found them to be good people. I am glad now that Dixon lived.

But I still can’t bring myself to have the same feelings about George Cornell. As Charlie Richardson said in a newspaper article recently: ‘Cornell showed a lack of respect. He had to pay the price . . . Respect was what we were all about, like the Krays. When we were put away the real crimewave started. In our day we had no mugging and no local burglary. You could safely leave your front door open when you went out. If anyone did step out of line, they simply got a smack in the mouth.’ Our sentiments entirely.

The end of Cornell marked the beginning of the next great Kray coup – the freeing of the Mad Axeman, Frank Mitchell, from Dartmoor. A feat considered impossible at the time. But, after Cornell, we believed that anything and everything was possible.

5

RON: THE TRUTH ABOUT THE MAD AXEMAN

The greatest coup, the most brilliant stunt, ever pulled by the Kray twins, came in 1966, when we managed to free a con known as the Mad Axeman from Dartmoor prison. His real name was Frank Mitchell and he was an extraordinary man – 6 feet 3 inches tall, with huge hands, a dagger tattooed on his left arm, a massive physique, great boxing skills, and a heart of gold. He wasn’t mad and he wasn’t even a skilled axeman. He got his nickname because once, when he was short of readies, he was said to have threatened some people with an axe so that they would give him money. In fact, although he had the strength to tear two men apart at the same time with his bare hands, he wouldn’t hurt a fly – he was truly a gentle giant.

Reg and I felt sorry for Frank because, although his crimes weren’t serious, the authorities had locked him away without giving him any date for his release. Further-more, they had stuck him in Dartmoor, just about Britain’s most primitive gaol. I had made a promise to Frank that we would get him out of there, though, to be honest, I never really thought he would take me up on it. But then we received letters from him passed on by friends who visited him, saying how desperate he was getting, how the prison governor refused to see him to discuss his problems, and how he wanted us to help him escape.

That was easier said than done. An escape from Dartmoor seemed a tall order. The prison is set in the middle of some of the wildest and boggiest moorland in the country. Few prisoners have managed to escape from it. Anyway, Reg and I sat down to discuss Frank Mitchell’s plea. After a good chat we decided to give it a go. After all, we had made him a promise, and if we could spring him from Dartmoor, it certainly wouldn’t do our reputation any harm.

The idea, at that stage, was to spring Frank from Dartmoor, bring him to London and hide him in a secret flat. While he was there we would arrange for letters to be sent to the national papers and the Home Secretary saying that if Frank’s case was reviewed he would return voluntarily to Dartmoor. If the authorities wouldn’t agree to consider his case, then we would make sure he got away. It was a tall order and, looking back, maybe it was a crazy thing to attempt, but at that time we had so much power and so many powerful people in our pockets we felt we couldn’t go wrong.

Reg decided that he would personally recce Dartmoor to see what the prospects were. So he wrote to the governor – using a false name, of course – asking him if he would like a visit by the great ex-boxer Ted ‘Kid’ Lewis, who would give a talk to the prisoners about his boxing career and show films of his old fights. We hired the films from a film distribution company in Wardour Street. We soon received a letter from the governor saying he would be delighted to meet Ted and was ‘thrilled’ that Ted would be giving a talk to the prisoners.

A few weeks later Ted and three ‘associates’ (i.e. Reg and two other East End villains with criminal records as long as your arm) made the journey by road to Dartmoor. Needless to say, Reg and his companions had disguised themselves as much as possible, just in case. Luckily it was raining hard, so they were rushed through the courtyard of the prison and not checked out properly. Eventually they reached the area of the prison where the films were to be shown. The projector and screen were erected and the show began.

The Dartmoor cons loved Ted and gave him a standing ovation. Ted himself wept with emotion – by this time dear Ted was in his seventies.

During the show Reg and the other two ‘associates’ were sitting in a gallery overlooking the stage and all the cons. They were having a really good look round when some

of the cons in the audience recognized them and began waving at them. Frank Mitchell, of course, ignored Reg.

One of the prison warders sitting near Reg turned to him and said, ‘Where do you know those blokes from?’

Reg pointed to one of the two villains he’d brought along and said, ‘I don’t know them at all – but I believe they think he is Norman Wisdom.’

‘Oh yes,’ said the screw, ‘yes, even I can see a likeness.’

After the show the governor and the padre took Reg, Ted and the others for a meal. The governor seemed to enjoy telling Reg about the various convicts he’d had under his wing. They even spoke about Frank Mitchell, whom the governor called ‘a sad case’. At the end of the meal they all shook hands and the governor asked Reg if he would bring Ted Lewis, or some other great fighter, back to the prison. Reg said he would do his best. He certainly hoped to be back at the gaol in the near future.

I know all this sounds incredible, a figment of my imagination – but it really happened. Mind you, a lot of the things which were happening in Dartmoor at that time were quite incredible.

When Reg came back to London and told me what had happened, we decided that freeing Frank Mitchell was going to be easy. And it would certainly get the country talking.

We weren’t quite sure when to pull the job but then, to our surprise, we got a phone call from Frank that made up our minds for us. The call was made to my flat at Cedra Court and Frank said, ‘I can’t take any more uncertainty, Ron. I must escape. Remember your promise to help me. If you don’t help me, I’ll break out by myself.’

A week later, on 12 December 1966, two of our top men, Albert Donaghue and Mad Teddy Smith, drove down to Dartmoor on a morning when we knew Frank would be on an outside working party. He slipped away from the other prisoners and when Albert and Teddy found him he was contentedly feeding the moorland ponies. They bundled him into the car and raced him back to London.

Our Story

Our Story