- Home

- Reginald Kray

Our Story Page 3

Our Story Read online

Page 3

One of those involved in that punch-up was a lad called Dennis Seigenberg. Many years later, in 1969, I met him again in the special security block in Parkhurst prison. We were both at the start of life sentences. He hadn’t changed a lot since I’d last seen him, but his name had. He was now calling himself Dennis Stafford and he’d been convicted of killing a fruit-machine salesman.

That appearance at the Old Bailey was the start of a long war between Reg and Ron Kray and the law. It was a war they eventually won – though we won quite a few battles along the way.

It was also the beginning of the end of what could have been a good boxing career. When I was sixteen I had seven fights as a professional and won them all. There wasn’t the big money in boxing then like there is now, but I was good and I could have done all right. But managers and promoters don’t like boxers who get into trouble with the law. Suddenly, in boxing circles, the name Kray had become bad news. So I just thought: Sod ’em. If I can’t make a living one way, I’ll make it another. I’d had too many years hungry. So had Ron. We had no intention of being hungry any more.

RON: BORN TO HANG

In the East End, when we were kids, you really had only one of two choices if you wanted to make anything of yourself in life: you either became a boxer or a villain.

You always got the odd exception to the rule, of course. One of the kids who used to come to our house in Vallance Road was called Kenny Lynch, and he went on to become a good entertainer. He even got an MBE, which is pretty unusual for an East End backstreet urchin. Good luck to him, he was a great little fella. But we weren’t properly educated, so there weren’t that many options if we wanted to make a bob or two.

Our heroes were always boxers or villains. Our biggest hero was Ted ‘Kid’ Lewis, who was champion of the world at three separate weights. He grew up just round the corner from us and we worshipped him.

But we also really admired the famous local villains, like Jimmy Spinks, Timmy Hayes and the greatest of them all, Dodger Mullins and Wassle Newman. All great fighters, but in a different way to Ted. They were East End villains of the old style. Fearsome, tough fighting men who didn’t give a toss for anyone. Even the coppers were scared stiff of them. They ruled the streets of the East End when we were kids, but they always played by rules which we admired. They never hurt women or kids or old people – they only ever did damage to their own kind. That was the code by which Reggie and I lived and we still believe it was right, even though we paid a high price for it.

Wassle Newman was the biggest man I ever saw, a giant of a man, with a beautiful set of white teeth, which he used to keep in good condition by chewing huge crusts of bread. One night he stopped at a tea and coffee stall in the East End – one of those wooden stalls – and he asked for a cup of tea and a crust. Well, they didn’t have any crusts and that annoyed Wassle. So he got a length of chain and tied one end to the stall and the other end to a tram that was parked nearby. When the tram moved off, so did the stall. The whole lot moved a few yards, there was a bloody great bang – and then the stall collapsed in a heap. And the guy who ran the stall was still inside it. He was well pleased, I can tell you. But he took one look at Wassle and decided not to make an issue out of it. He was wise. You can always buy a new stall – it’s more difficult to get a new face.

Dodger Mullins, though, was the real guv’nor of the East End in those days. My dad used to say he ran the area and most of the thieving that went on at that time. Most people steered well clear of Dodger, but he was always kind to me and Reg and the other kids in the area.

Another hero was a tough guy called Harry Hopwood. He used to be at Vallance Road a lot when we were kids and he had been the best man at our parents’ wedding. He used to sit us on his knee and get us to drink from bottles of brown and light ale. Years later he gave false evidence against us in court to save his own skin. Later I heard he’d died an alcoholic, which I thought was poetic justice. I wonder if, in his later years, when he knew he was dying, he ever thought about those little twins he used to bounce up and down on his knee.

So you see, when we were young, we were brought up against a background of fighting – a background of violence, if you like. There were always plenty of fights in the pubs and regular battles between the villains of Bethnal Green and the villains from other areas, like Watney Street in Whitechapel. The police rarely intervened in these scraps for the simple reason that they didn’t want to get hurt themselves.

Our own family produced a lot of fighting men. They used to call my father’s father Mad Jimmy Kray, because of his fierce temper and fighting ways. He had a clothes stall in Brick Lane market, and Reg and I sometimes used to help him load and unload his stuff. We’ve still got the medals he won for bravery in the First World War. He was a very brave man. They all were – fierce, aggressive, nasty maybe, but very brave.

My great grandfather’s name was Critcha Lee. He was a gypsy, a cattle dealer from Bermondsey. He died in Claybury madhouse, and so did my grandfather’s brother, whom they called Jewy. It seems that gypsy blood and madness have always run through the family.

Reg has spoken about John Lee, my grandad on my mum’s side, the man they used to called the Southpaw Cannonball. He wasn’t just a great fighting man, he was also a showman, an acrobat and juggler. He lived till he was ninety-eight and he was probably the most amazing man I’ve ever met. I even wrote a poem about him which I dedicated to the memory of grandad. It was called ‘He Was a Man’.

First and foremost he was a man.

He had seen the gaslight era,

The Blitz,

And caught a glimpse of the permissive society.

Had done most things in his life.

Fought in the ring,

Danced on stage and would sing,

Leapt from barrels

And through rings.

Was around when Bob Fitzsimmons beat the great John I.,

Worked hard and fought well.

Could play most musical instruments,

Even licked a white-hot poker for fun,

Liked all sports

And would jump and run,

And always had a great story to tell.

Yes, he was a man.

He never knew the word of fear,

We loved him dear.

His precious memory we will keep.

He went to sleep in his ninety-eighth year,

God bless him and may he rest in peace.

Not the best of my poems maybe, but it sums up the kind of man he was, the kind of man you just don’t find any more.

I admired all these men, but the two people I really loved were both women – my mother and my Auntie Rose.

My mother was simply a wonderful woman. No man ever had a finer mother. We often had no money and very little food, but she always made sure that Reggie and Charlie and I had something to eat and something half decent to wear. She always seemed to be cooking, washing or mending for us. She never gave in to despair or frustration, even when times were bleak and the future seemed to hold nothing. Even now, as I sit here in Broadmoor, wondering how it all went so wrong, I can still remember my mother holding me in her arms when I was little. I can still remember the smell of her soap. She was always spotless, even in all the grime and filth of the East End. She was the most placid woman I ever met. I never had an argument with her, we never answered her back, and I’ve never had a bad word to say about her. I would kill any man who spoke ill of my mother.

She loved making people happy. She used to tell me that God pays debts without money. She was always thanking God when something good happened.

And she was scrupulously fair. Sometimes Reg and I used to compete for her attention, to get in her good books the way kids do, but she would have none of it. We were always equal in her eyes. As well as a great closeness between Reg and me, there was always a bit of rivalry. One twin never wanted to be outdone by the other. Maybe that philosophy has added to our problems over the years, perhaps we’ve

done unnecessary things just to prove to the other that we weren’t chicken.

I also loved my mum’s sister, my Auntie Rose, who lived round the corner from us in Vallance Road. She always had a soft spot for me; I think I was always her favourite from the time when I caught diphtheria when I was very tiny and nearly died. She was a much harder woman than our mother, much tougher, and she wasn’t frightened of any man, but she was always gentle with me. One day the kids at school had been taking the mickey out of me because my eyebrows were different from theirs – they went right across my nose and joined in the middle. I was upset about this and I asked my Auntie Rose why my eyebrows were like that. I’ll always remember what she said: ‘It means you were born to hang, Ronnie love.’ As it happened, she was very nearly right. Perhaps it would have been better for me if her prediction had come true.

I don’t have quite such happy memories as Reg about our father. During the periods he was at home he would often drink too much and come home and start shouting. This used to upset me and I used to think that one day, when I was bigger, I would give him a bloody good hiding – and later I did. Even as we grew up, when Reg and I started boxing and were training really hard, he would still come home drunk late at night and wake us with his shouting. He wasn’t a bad man. But when he’d had a drink he got a bit silly. Looking back, though, times were so hard then that it’s not surprising that blokes took to drink.

When war was declared and my father went on the trot from the army we were only six, but on the occasions when he did come round to Vallance Road he told us that if the police came looking for him we were to tell them that he had left home, that he wasn’t living with our mother any more. And he used to send us round the corner to the tobacconist to buy a newspaper, just to see if there were any coppers hanging around.

At that time he was living in a room in a house in south London with an old pickpocket called Bob Rolphe. Reggie, Mum and I would go over and see him in his room in Camberwell.

On two occasions he was actually at home at Vallance Road when the police called. One time he hid beneath the kitchen table, hidden by the tablecloth, while Reg and I were having our tea. He stayed there while a copper questioned us about our dad. We were both frightened but we gave nothing away. That was the first – and last – time a copper ever frightened me. Another time he was hiding in a cupboard and as a policeman was going to open the door I shouted out, ‘You don’t think my dad would hide in there, do you?’ The copper shrugged his shoulders and went to look somewhere else.

Our mother tried to bring us up properly, but with a background like that it was impossible for us to have any respect for the law. It was always a case of them or us. Times were dreadful really, but I found the war ever so exciting. I loved the sound of the bombs and all the noise.

Shortly after war was declared in 1939 we were evacuated with our mum to a farm at Hadleigh in Suffolk. Reggie and I loved it there – we ran wild in the countryside. To this day we both love the smell and the feel of the countryside. But our mum missed the East End and all her family, so back we came to the East End.

I can still remember vividly the sound of the sirens going and Reggie, Mum and me going into a pitch-black street. I can remember seeing the searchlights in the sky and hearing the bombers overhead. I can remember the bombs dropping and us running to the air-raid shelter, an old railway arch, where we used to take cover. Everybody else was frightened, but I loved the excitement of it all.

I’ve always loved a good scrap, no matter who was involved. My mother used to tell us to say our prayers that the war would end, but I can remember praying that Adolf Hitler would get smashed by a bus. I told my mum, but she said it was wrong to pray for things like that, even though Hitler was a bad man. That sort of comment was typical of my mum.

I can remember, in Cheshire Street, just a street away from ours, one of Mosley’s Blackshirts slagging off the Jews, and my grandfather arguing with him. God, the drama of it all, the colour, the sheer fucking excitement. I loved it. We kids used to play on the bomb sites and the dumps, staging our own wars. We caught scabies more than once and the medical officer came and painted us. We had great battles with kids from other streets, chucking all sorts of things at each other.

But it had to end and, when the war was over, we started proper schooling at Daniel Street. We also joined a small youth club in the Bethnal Green Road, run by the Reverend Hetherington, the man who helped Reggie when he got into trouble over the slug gun in the train. He was over six feet tall and very powerfully built. We never went to his church but we really liked him and often did odd jobs for him. We were a tough, unruly bunch of East End kids, but the Reverend Hetherington really knew how to handle us.

Funnily enough, we were happy at school too. It was never quite exciting enough for Reg and me, but the kids were encouraged to box and play football. We had a great football team. An East End newspaper has recently printed some pictures of the Daniel Street team of the time and called us ‘the Liverpool of the thirties and forties’. The article says: ‘The boys of Daniel Street, for many years, won everything – except the wooden spoon.’

There were pictures, too, of some of our old teachers – Mr Bell, Mr Faulkner and Mr Evans. They were good blokes and they knew how to handle us, old Bill Evans in particular. He was a teacher at Daniel Street for thirty years. He was a Welshman and we took the piss out of him for that. But he didn’t mind, and if we went too far we got a good belt round the head. But it worked. There was a bloody sight more discipline then than there is in schools now. In one article Bill Evans was quoted as saying: ‘The Kray twins were the salt of the earth. Never the slightest bother as long as you knew how to handle them. They were all right.’

Mind you, even old Bill Evans never sussed one of our tricks, and that was, if one of us was in trouble, he’d pretend to be the other one. We always used to confuse teachers like that. If a teacher would scream, ‘I want a word with you, Reg,’ then Reg would look up innocently and say, ‘But I’m Ron. I’m sorry but I don’t know where Reg is!’ By the time the teacher had eventually found the one he was after, he’d generally cooled down. It was a trick we pulled many times in later life – both with the army and the law.

Of course, there were fights at school. Reggie and I were evil little bastards when it came to a scrap and we would always make sure that the other kids came off worse. But we had to – even at school it was a survival of the toughest. But, as Reg says, we were never the children of the Devil that some people have painted us.

I don’t know how many of our old teachers are still alive, if any, but as I write Father Hetherington is still alive, although he’s now a very old man. But if he reads this, I would like him to know that we still think a lot of him and we hope that he still has some fond memories of us.

Actually, Reg’s slug gun incident apart, there was no more trouble with the law until we were sixteen. Sure, there were one or two warnings about fighting, but all the kids then used to get into scraps. What else would you expect? We came from a rough environment, we never had the benefit of a good education or facilities like sports halls and all the other things that kids today get. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t resent today’s kids and all the advantages they’ve got, but we were lucky to have food and clothes and a roof over our heads.

As I said earlier, if you came from our part of the world you were either going to be a boxer or a villain – and it looked as though all three of us, Reggie, Charlie and me, were all going to be good boxers. My older brother Charlie was welterweight champion of the Royal Navy. When he came out of the navy he boxed as a professional. He had twenty-five fights and lost only four of them.

The trouble with Charlie – and this is funny when you remember we are talking about a member of the Kray family – the trouble with Charlie is that he was too easy-going. He just didn’t have enough of the killer instinct that champion fighters need. That’s not a personal criticism – either you’ve got it or you ain’t. Charlie was,

and still is, a lovely, mild-mannered sort of bloke. I’ve only ever seen him lose his temper once – and that was the night he knocked out Jimmy Cornell, George Cornell’s brother, in a club we owned called the Double R. Later I knocked out George Cornell himself – but rather more permanently. Those Cornells had a knack of looking for, and finding, big trouble.

When it came to boxing I was just the opposite of Charlie. I was a bit too aggressive, a bit too keen to get ’em flat on their backs and get the fight over with. But I didn’t do too badly. I didn’t get beaten much as an amateur and when I turned pro I won four fights out of six. I was a welterweight in those days.

But Reggie was the real star. London Schools Champion, virtually unbeaten as an amateur and, when he turned pro, he won seven out of seven as a lightweight. Reggie could have gone all the way, and I think in some ways it was my fault that he didn’t. If one of us was going to get into real trouble with the law, it was always going to be me. There was something about my nature: if someone did something or said something which I didn’t think was right, I’d slug ’em and that would be that. I loved my family and my friends, but I couldn’t give a toss for other people. And I hated coppers ever since I was a nipper and they used to come round to our house looking for our dad. With an attitude like that, chances are you’re going to get into bother sooner or later.

Reggie was different. He didn’t always think like that. He liked a more peaceful life. But he was my twin, my other half. We looked the same, we thought the same. If I had a problem, he had a problem and vice versa. If I had a pain, he had a pain. And if I had an enemy, he had an enemy. So when I started getting into bother with the law, Reg was bound to follow me. He had to, he had no choice. It was like the law of nature. I hope I’m making myself clear, but maybe you’ve got to be one half of identical twins to know what I’m saying.

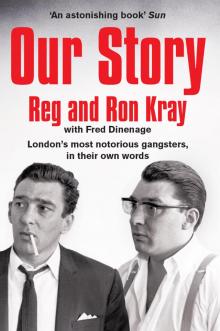

Our Story

Our Story