- Home

- Reginald Kray

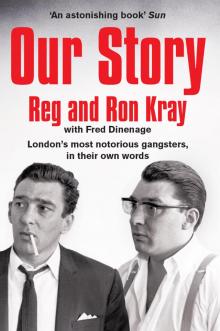

Our Story Page 16

Our Story Read online

Page 16

Any prison society is made up of a number of strangers massed together, allowing that there is a small minority who already know each other from the outside world. Bearing this situation in mind, it is pretty obvious that there will be good reasons for distrust. The criminal world contains theft, vendetta, murder and various other forms of crime, so most inmates will have good reason to fear betrayal by a fellow con, who may be seeking to curry favour with the prison officials in the hope that he may be granted parole or some other form of reward for supplying information. I am not suggesting that the parole board makes deals with this type of inmate, but this is the sort of reward that informers are seeking.

I often think how nice it would be to live in a non-criminal environment where you could relax and socialize with your neighbours and take part in everyday, normal conversation, without being overly concerned about what you say. You can, and should, be able to socialize as much as possible in prison, and yet still keep within your own circle.

All long-term prisoners go through periods of suffering from loss of identity. To understand this you only need to look at people like Sir Francis Chichester, who, after a year at sea alone on his yacht, could not converse properly on his arrival home. He was suffering a sort of personality disorder brought about by being in total solitude.

There is also the case of the Englishman who was arrested in Russia for spying. He was in solitary confinement in a Russian prison for eighteen months and nearly went insane. He wrote a book about his experiences and his fight against insanity. Now, if you compare his eighteen months in solitary confinement with a life sentence with a recommendation of a minimum of thirty years, much of it in maximum-security, Category A conditions and some of it in solitary confinement, you will get some idea of what I – and others – are up against. It is one hell of a hill to climb, one hell of a battle to fight.

But I have fought it, day by day, month by month, year by year. I know the authorities, the Home Office, won’t be happy until they’ve pushed me over the limit. But they are wasting their time, they won’t succeed. I have studied for mental progress and inner calm for many years. It has not been easy. But I believe I have succeeded. I no longer hate people. I bear no malice against the people who put me here – the police and the judge – though I feel they were too severe. Also, since beating my paranoia, I feel I do have many friends, I feel the world and life can hold hope for me. Looking back over those bad years reminds me of an old proverb: ‘A thousand years have passed by since yesterday.’

I met kids in Parkhurst whose fathers I knew as young men. One young fellow even asked me what his dad was like. His dad had been in the security block with me many years ago – around 1970 – but had died in prison. All these years later, his son wanted some memories of a dad he barely knew. Sometimes prison life can be bitterly sad.

There are so many young cons in Parkhurst, and that saddens me as well. Not too long back another prisoner said to me about one of the young cons who’d just arrived, ‘Watch him. He’s a bit of a nutter. He thinks Jack McVitie is his father. He could be after you.’ I made a meet with the young con in my cell and told my friends to disappear while I spoke to this young guy. I gave him a cup of tea, let him relax, and then asked him point blank if there was any truth in the rumour that he was the son of Jack the Hat. He assured me it wasn’t true. He also assured me that he bore me no malice of any kind. So that was another possible confrontation to cross off my list.

I have met other young kids whose fathers were enemies of mine, yet I have got on well with all of them.

I feel very sorry for young cons. A long-term sentence is not the answer for any young man. It’s no wonder that so many of them turn to drugs, particularly to cannabis. Some of them have told me they would crack up, commit suicide, were it not for the relief that cannabis brings.

I myself am very worried about the spread of cannabis – not only in prisons but also in society in general. Cannabis has given many young people who are out of work and redundant a means of finding relaxation from the days of despair. But it also acts as a social bond for those united in adversity – those who see the establishment, and particularly the police, as the enemy. People now enjoy the intrigue and pleasure of smoking joints of cannabis at social gatherings in just the same way as people in America in the 1920s enjoyed their bottles of Scotch in Prohibition times.

In the 1960s this country, and in particular London, had illegal gambling which, again, was anti-establishment, and again the intrigue, the element of law-breaking, was a great attraction for those who took part. Gambling in the sixties brought a certain amount of glamour to the London scene – Ron, Charlie and I capitalized on this and made a small fortune. Billy Hill was perhaps the first to spot the enormous potential, the rich pickings, to be made out of people’s desire to gamble, often in the seediest of surroundings. Some of the top people in society enjoyed this particular vice as much as those in the lower classes. We witnessed fortunes won and lost in a single evening over the turn of a card. But the fortunes that changed hands this way were nothing to the fortunes being made by the dealers in cannabis and other drugs. There is a ready-made market place for these drugs in prisons and – make no mistake about it – a lot of drugs are smuggled into prisons.

And maybe in some respects it’s just as well that they are – for without the calming effect that drugs have on many prisoners, I am sure there could be full-scale anarchy in our gaols.

Every week I get other cons telling me they are going out, going home – either on home leave or going out for good. But that is never the case with me. Years ago other prisoners would never do this to a lifer – they would never speak of going free to a man who was facing years being locked up. But now it seems all forms of respect are diminishing in the world, even in prison. I don’t mind other people talking about home leave and freedom, in fact I’m usually pleased for them, but their talk takes its toll on me.

It’s even worse for Ron because he lives in a world of total doom, I always come away totally depressed after visiting Ron. How he manages to remain so cheerful living in a place like Broadmoor amazes me. Like me, he relies heavily upon letters and also upon visitors. Without visitors, without the friends who come to see you, you are lost. All kinds of people come to see me and to them all I am very, very grateful.

It’s extraordinary the friendships you make in prison. My closest friend at Parkhurst was Pete Gillett. He was in cell 13 and I was in cell 14. On the door is your name and number and religion. They used to write on a board how many years you were in for, but they’ve stopped doing that now. I don’t know why – perhaps to stop you getting even more depressed at the thought of the wasted years.

Pete Gillett is a young man – twenty-six, as I write – from Crawley, in Sussex. He was jailed for six years for conspiracy to rob. His best friend ratted on him to the police to save his own skin.

He was very bitter when I first met him – bitter about his circumstances, bitter about the guy who’d set him up, and bitter about his wife whom he’d split up from. The only good thing in his life seemed to be his son, Liam, whom he idolized.

We became friends and I would like to make it clear that that’s all there ever was to it – friendship. It may sound corny but I became the father Pete never really had – he comes from a broken home – and he became the son that I’ll never have.

We’ve helped each other. He forced me to pack up smoking; I forced him to start thinking positively, to develop his interest in music. And as a result he’s now a free man. He’s become a professional singer and has released a record. He still writes and comes to see me regularly.

It was Pete who saved me from a good hiding one day at Parkhurst. I was watching him play in a football match when, without my noticing it, a gang of about six began creeping up on me. One of them was a distant relation to George Cornell, the guy Ronnie killed, and he must have thought that if he couldn’t get Ron, then he’d do me over instead. They were just about to pile in

on me when Pete noticed what was happening. He shouted a warning and came running over, boots flying. It was a right old dust-up. Another couple of cons joined in on our side and we finished up the winners – even though Pete did collect a beautiful black eye.

That’s the thing about prison life – you need eyes in the back of your head if you are a name prisoner like me. There’s always someone who fancies his chances. However, friendships like the one I had with Pete make life more bearable.

I’ve also made friends, over the years, with other, less likely people. For example, several years ago the padre at Parkhurst was a man called Hugh Searle. He was, and still is, a most compassionate man. Ron and I got to know him well and he was always kind and helpful to any cons in need. On one occasion he took some tobacco from me to a con who was in the punishment block. This was most unusual for a prison padre, but much appreciated. He was much liked by the cons and would sit, quite relaxed, in the cells of some really vicious individuals. Yet he seemed to get along fine with all of them.

I was sad when he left to take up another post in Cambridge. But I feel some of the prison staff and certainly the prison authorities were delighted to see him go – he was far too liberal from their point of view. But, to this day, he stays in touch with Ron and visits him in Broadmoor. He is very much a man from the other side of the fence, and yet still a man I am pleased to count among my friends.

Then there is Watson Lee, a magistrate who lives on the Isle of Wight. He was often summoned to Parkhurst to officiate at the Board of Visitors’ hearings – in other words, to deal with offences committed by inmates of the prison.

I first met Watson Lee about fourteen years ago when I was sitting before him on a charge of malicious wounding against another inmate by the name of Roy Grantham. There had been trouble between Grantham and me which started in my cell, which was located, at that time, in the special security block. Grantham had been transferred from Gartree prison because he was such a bully and troublemaker and it was thought that Parkhurst was the only place that could handle him. He had a reputation as someone to be avoided if at all possible. I knew of his reputation and knew that, as I was king of the Parkhurst cons, he would almost certainly make me one of his first targets. But I decided to keep an open mind and made him welcome on his arrival. This was a mistake. I should have paid attention to the prison grapevine which indicated that he was a true bully and would mistake kindness for weakness.

Grantham soon set about tormenting me. I could only tolerate this by suppressing my anger, but I knew my patience would only hold out for so long. The screws knew this as well, so they deliberately made sure we were close together as much as possible. They knew that would guarantee trouble, sooner or later, and give the nasty ones among them the chance to put the boot in on either Grantham or Kray or both.

One of Grantham’s habits was to walk into my cell when I was eating a meal. He would pick, at random, some food off my plate and stuff it into his mouth, like a pig. Another of his habits was to lean over the door of the toilet and start a long, boring conversation while I was sitting there. The toilets in Parkhurst have half doors, and so Grantham not only bored me but embarrassed me as well, because during our one-sided conversation he would also stare at me during my act of ablution.

Why didn’t I tell him to bugger off and, if that didn’t work, why didn’t I clock him one? Well, I’m talking here about a man who was half mental. I have never been a coward but with a man like Grantham you have to pick your moment very carefully, otherwise you would get very badly carved up indeed. It had happened to several other cons he’d picked on. Also, he was a big man, over six feet tall. He was a keep-fit maniac, who would drink jugfuls of carrot juice and go around the exercise yard with a towel wrapped round his head and his hands wrapped in bandages like a fighter in training. Everywhere he went he would be shadow-boxing and grunting. Although I could see the humorous side to this, I knew the situation between Grantham and me would end up serious.

The story ended one morning when he came into my cell and started to issue threats because he thought I had slighted him the previous day. His language became more and more abusive and other cons were listening. This was the moment of truth, there was no backing down. Either Reg Kray or Roy Grantham would walk out of that cell. The one who walked out would be king – the other would be flat on his back.

Grantham had a knife which he was waving around, but I never needed weapons. While he was shouting and raving, I picked my moment and smashed him harder in the face than I have ever hit anyone. He went down and I made sure he stayed down. He was badly hurt. Out of loyalty to a fellow con – even though I hated him – I got rid of his knife.

A few days later I was up before the magistrate, Watson Lee, putting up my defence for hitting Grantham. I thought I had a good case and I thought I delivered it well. Mr Lee listened to my case intently. At the end of my submission he looked slightly amused and said, ‘It seems that Grantham should be accused, instead of you.’ He then paused and said, ‘I am awarding you fifty-six days’ punishment, which will start today.’ I was angry, but I had developed a certain liking for Watson Lee. He had given me a fair hearing. The punishment was a bit excessive – but that’s been the story of my life.

This friendly rivalry between myself and Watson Lee continued over the years when there were one or two other bits of bother. Ever since the year of the Grantham affair, Watson Lee and I have sent each other Christmas cards and whenever he was at Parkhurst he would always come and see me in my cell for a chat. We exchanged points of view on a wide range of subjects. He’s a man from a totally different world to mine – but a man I admire and a man I am pleased to call a friend.

As for Roy Grantham, in later years he became a super-grass and put many of his friends behind bars. Eventually he committed suicide.

I have always believed that some good will come out of even the worst situations, and the fact that I have made friends with men like Watson Lee and the padre, Hugh Searle, proves this to me.

Funnily enough, it was Watson Lee, I think, who recently sent me a cutting from one of the East End newspapers. Under the headline, ‘Publican’s Nostalgia for Krays’, the writer, a journalist called R. Barry O’Brien, wrote:

An East End licensee who claims violent crime in his neighbourhood has made people afraid to go out to pubs at night, looked back with nostalgia, yesterday, to the days twenty years ago when the gangster brothers Ronnie and Reggie Kray ruled London’s underworld.

He quoted Eddie Johnson, licensee of the Two Puddings public house at Stratford, as saying, ‘Compared with some of the villains today the Krays were thorough gentlemen, respected and even admired by many people.

‘They were nasty to their own kind, but they left ordinary people alone. Today’s villains are nasty to everyone – old, young, middle-aged. They make no distinctions.’

Thank you for the kind words, Mr Johnson. It’s what Ron and I have claimed all along, but it’s done us no good. The authorities need us as scapegoats.

Parkhurst prison has broken many men in its grim history, but it didn’t break me. But right to the end of my stay at Parkhurst the authorities cheated me. I was summoned, early in 1986, to the governor’s office and told that I was being sent to Wandsworth prison in London ‘for some weeks’. I was furious because there was no reason to send me away and break up the friendship I had built up with Pete Gillett. Besides, in a tough nick like Wandsworth someone like me is a sitting target for any young thug who fancies making a name for himself. I’ve no worries about defending myself but – as I’ve learned to my cost over the years – you defend yourself and still finish up in the punishment block.

I protested bitterly but was told, ‘It’s in your best interests to go to Wandsworth, Reg. The authorities want to try you out in a different environment and then, if you handle it all right, you’ll be moved to a softer prison, either Maidstone or Nottingham. And you know what that means. The end of your sentence could be in sight.

’

It was all a lie, as it turned out, but I fell for it. I allowed them to take me away from the best friend I ever had. And suddenly I was on the way back to Wandsworth. The last time I had been there was when my beloved Frances and I were engaged. At that time, too, my dear mother and father were alive, and Ronnie and I were the rulers of London’s underworld. Twenty-one years had passed since then, and now I was back. But this time it was different. This time there was no Frances, no Mum and Dad. This time I was alone.

The sky above Wandsworth was dirty and grey and typical of London. The little cockney sparrows hovered, quite tame, around my feet, mingling with the London pigeons, as though to welcome me back to Dickensland as a fellow cockney. The little exercise yard at Wandsworth hadn’t changed much in all the years; neither had the cells. Yet so much had happened in between.

I thought to myself: it seems as if I have not come far in life. Yet I have walked a fast and hectic pace in between. And even though most of those years had been spent locked away, I had made many friends and learned more about myself than most men do. I had learned how to survive, mentally and physically, against the greatest odds.

Even though I was sad at Wandsworth, I felt my parents and Frances watching over me. It was as though the years had been condensed into the blinking of an eyelid, and I wondered where they had all gone. It would have been easy to be bitter. But I didn’t look back in anger because I know there are many others far worse off than me.

No one gave me any bother at Wandsworth. The screws were respectful and so were the other cons. They seemed to sense that I was at a crossroads in my life, that I didn’t need any extra hassle. So I was left alone to my thoughts.

The weeks passed quickly and uneventfully – maybe too uneventfully for the prison authorities. Reggie Kray, perhaps, wasn’t getting into the kind of trouble they thought he would in his new environment.

Our Story

Our Story